On Hearing Someone Say in Their Guidelines

They Do Not Like My Now Famous Student

I think of the glitz

of her verbs, her

retinas and fibulae,

flashy as we both looked

onyx hair to our buns.

Her Janis Joplin poems

were blood and not just

bBrocades, delicate

as anemone and with

that touch, holding on

and gulping spasm.

Sisters or maybe

twins, a city thought.

“Are you trying to win

the Lyn Lifshin look

alike?” a lean man sneered

before she sprinted in

to her own light. Both

of us always trying

to pare away, get rid

of what we couldn’t

use: 3 lbs, advertising

men. Her eyes like a

sailor’s trapped in

the lamp of a witch,

stunned at what she’s

concocted.

For Years She Could Smell Them,

Feel Their Feathers

pale in the wet grass,

trembling like kittens,

as light twisted the

leaves jade. She says

it was like picking

plums or roses, she

held them fluttering

to her lips. For weeks

she slept with them in

her hair. They were so

still then. Her mother

kept washing her skin,

the bureau they nested

in. Stone and beaks,

the dead birds like

a secret sister waited

for her to come back

from school. She said

the trees sang to them

after midnight. Years

later, their crumbling

shapes in chiffon and

silk like wedding cake,

stale crumbs on satin.

Their feathers, a wish

in code in a diary left

in the rain the blue

leaks from into lilies

and arbutus. For years

the wood smelled

like them

She Said She Was 13, She Wanted To But Not With

The Boys In Her Town, The Ones Who Knew

Her Family And Who’d Tell If She Did

So Lisa and I, well we decided to go

to the stinky part of town where boys

in leather, even at 6 ft tall, hung

back on their heels and seemed

to coil like snakes into their boots

so they were looking up at us. I wanted

to know what it was like. They’d

whistle and leer, grunt something

lewd. One Saturday we took the subway

south to where these hoods whose

names we couldn’t even pronounce hung

out and I held my breath. We paired

up with the most dangerous looking

ones. They lived at home but made a

hangout in a vacant alley,

pulled quilts and plastic over the

bricks to keep out rain. I went

in one corner and just did it. It wasn’t

great, it wasn’t horrid, kind of like

eating a spicy sausage when you’ve

lived as a vegetarian. Then I found out

Lisa chickened out, told her guy she

was on the rag. We went home. I

washed my hair all month, took

extra baths. I kept thinking how

next time my guy said he wanted me

to howl, take off everything, not just

my pants. I begged my daughter to

wait until at least she was out of high

school and tho you laugh, she did. She

was in college and when she called to tell

me, I could have hugged her over to tell

me, I could have hugged her over the line,

as I wanted my mother to that rainy summer

afternoon, be there

to hold me.

She Said It Was Her Mother’s Breasts

Pendulous, drooping down over the flab

that bulged up out over the girdle

that left ridges on her flesh,

almost welts. She tried to

sleep leaning over the bed,

wanted her nipples tiny and

rose, her breasts aiming

at star light. Mothers

ought to keep their breasts

like secrets whispered around

the dining room table in another

language so children shouldn’t

hear. It was too hideous. Forget

the gore in fairy tales, the

lewdness of thighs opening

and hair dripping. What

stinks doesn’t just make a baby.

Don’t she snarls, her pen digging

into paper, worry about Fanny Hill or

The Story of O, nothing she

says is as scary as those breasts.

It’s like death, like those

uncles and aunts, who clucked

and raised eyebrows at the

table and shook their graying heads

“no,” bolting up from graves they are

almost in the same positions as they

were around the table sharing what

they’d kept from me before

I want to know

She Drove Her ’79 Chevy Pickup

west from Laguna Vista,

slithered its metal cheek

to cheek with a rusted

Ford truck but didn’t

get out, just lowered

the window, slow as an

eyelid. Her skin glowed

in the moon like a

Texas cheerleader named

Ivory Baby in 1976 but

her tongue didn’t stop

and her lips sucked him

dazed past the ripped

up fender. Later in the

town’s one bar he wondered

what there was to do in

these parts. Could give

you the lowdown she flicked

in his ears, got out her

keys 12 miles from there,

shoving him off her. She

slid out of her seat into

a circle of lowered lights.

A cat howled and she yelped

with it. Other women came,

their teeth gleaming like

knives leading a dark

animal. He thought he’d

leave, but she had the

keys, could barely get

the visor down between him

and the moaning when he

saw her take something

long and dripping toward

the v of her jeans

turning the blue purple,

staining herself as if

she’d given birth

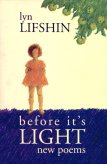

from my book:

Before It's Light - Lyn Lifshin

$16.00 (1-57423-114-6/paper)

$27.50 (1-57423-115-4/cloth trade)

$35.00 (1-57423-116-2/signed cloth)

Black Sparrow Press

Black Sparrow Press